Goal: to read primary medieval literature about love and war with sensitivity to literary and cultural contexts in situ, i.e. in Great Britain.

Goal: to read primary medieval literature about love and war with sensitivity to literary and cultural contexts in situ, i.e. in Great Britain.

Challenge: to understand the milieu of medieval literature, including the shaping role of medieval Christian culture, with attention paid to literary and historical questions.

Outcomes: Improved reading skills of primary texts: having read and understood primary texts through close reading, discussion, and challenge

Improved reading skills of secondary texts: understanding of, sensitivity to, and work with the primary issues regarding medieval literary texts

Improved writing skills via the production of group-organized and independent written work

Improved position as independent scholar through premier intellectual experience in Oxford

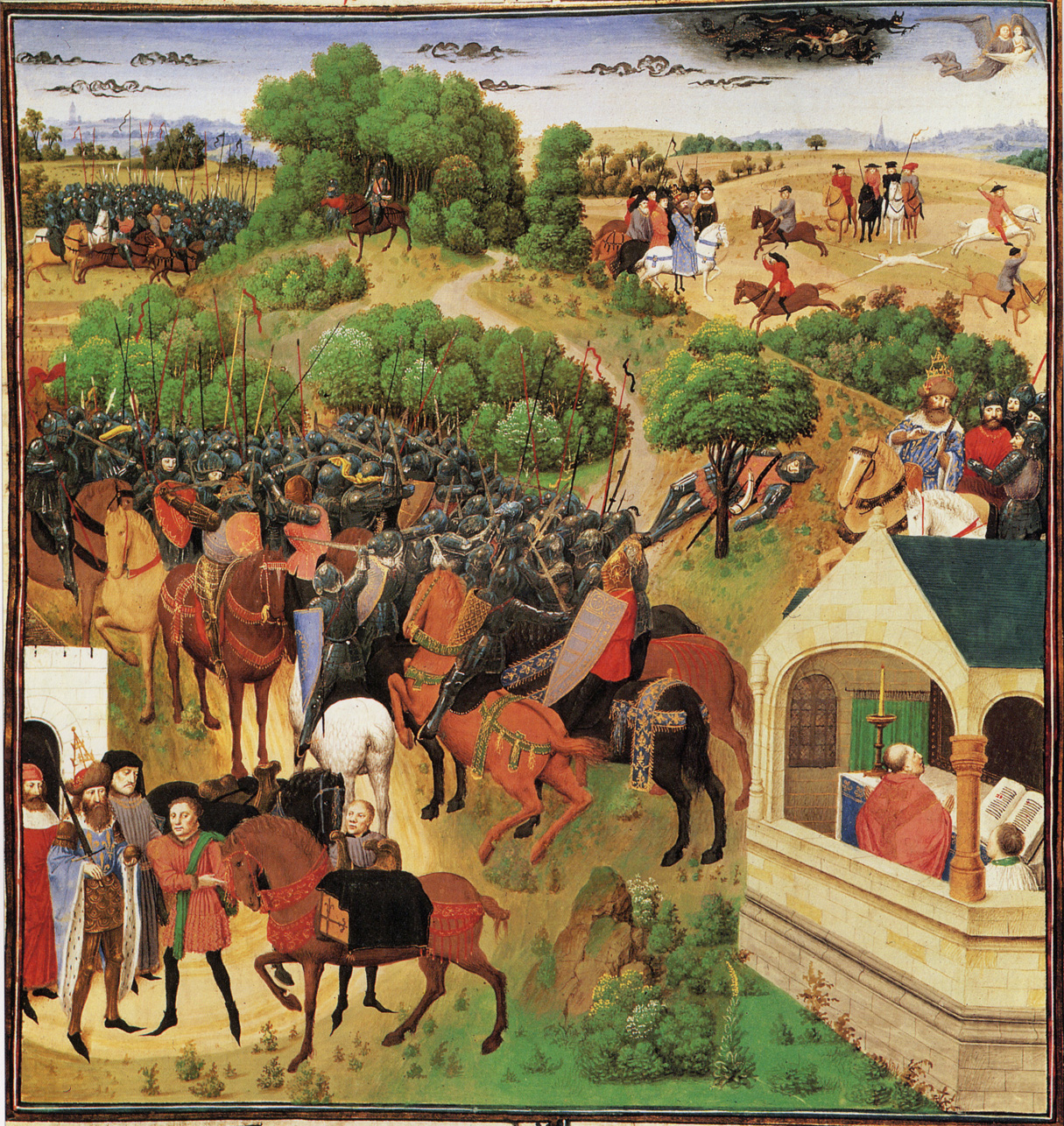

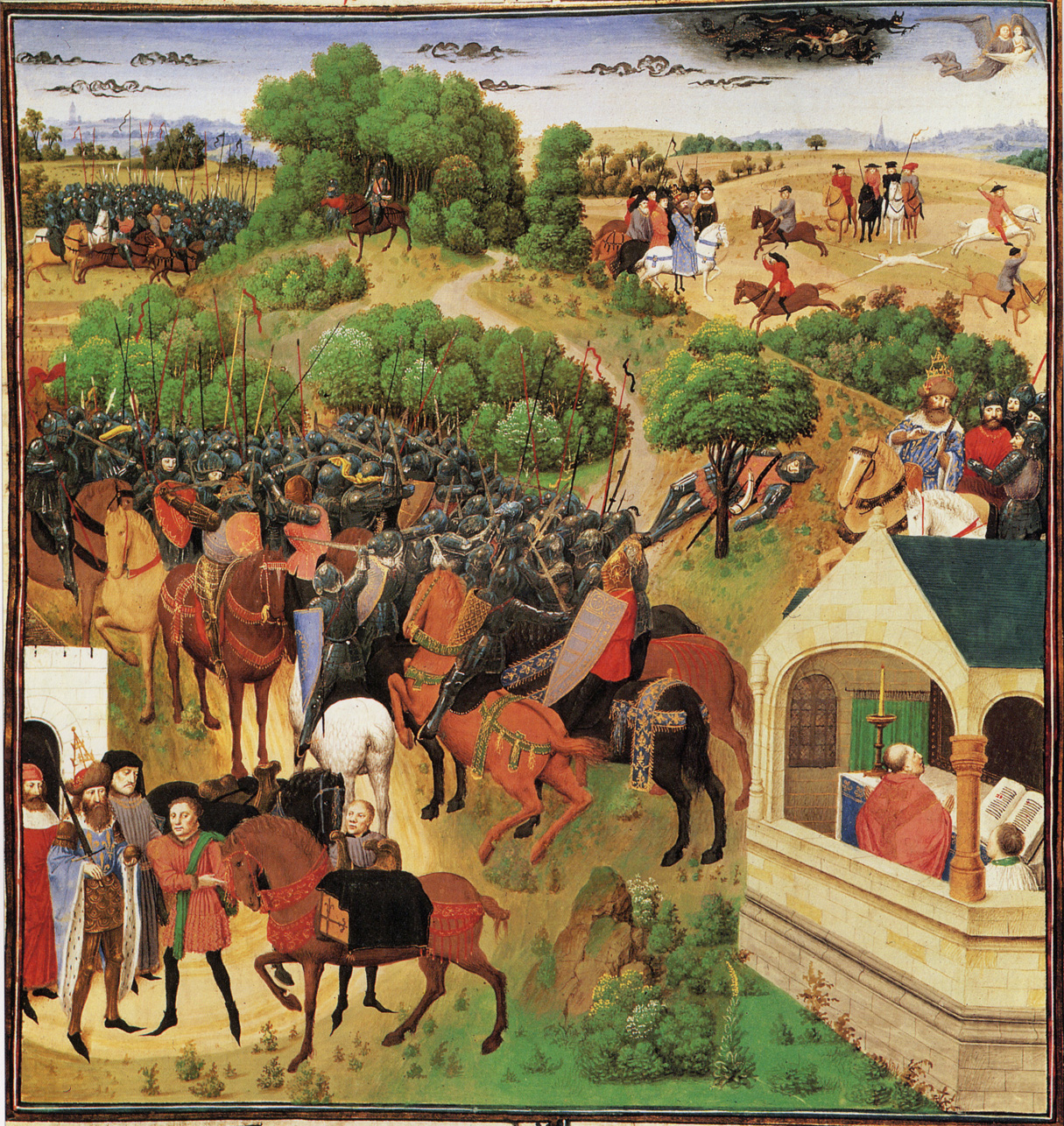

How did writers in the Middle Ages imaginatively express their understandings of and feelings about love and war, and how do we best understand their texts? How do the primary texts we’ll read present intersection(s) between love and war? Why is war used as a metaphor for love? Besides our primary texts, readings will include background in classical and Christian literary traditions and major literary critical statements on medieval poetry that treats love and war. The two literary modes we will initially articulate contrast epic with romance: we’ll see where those words come from and their current uses and abuses. We’ll primarily read poetry, albeit in translation (for the most part), and tangle with the thorny issue of “courtly love.” Along the way we’ll pay some attention to modernity’s inheritance of medieval themes, at the same time that we’ll honor the alterity of the Middle Ages as well as challenge received notions of the “medieval.” Course requirements include an introductory paper on a word, a reading log, a film critique, a group presentation with annotated bibliography, and a term paper.

Check out this helpful page about medieval studies research developed by the UO librarians.

Texts: BEOWULF, Seamus Heaney translation; SONG OF ROLAND, DuVal translation; LAIS OF MARIE DE FRANCE, Hanning and Ferrante translation; SIR GAWAIN AND THE GREEN KNIGHT, Borroff translation; MALORY, LE MORTE DARTHUR, Helen Cooper edition. Books have been purchased for the program and will be available at CMRS

Requirements

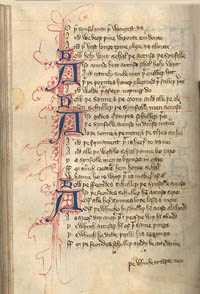

1. A brief exercise in Middle English language

- Choose one word from the following list.

War--Ted Medieval--Nayantara Nature--Sean Court--Augustine

Truth--Aaron Chivalry--Shannon Honor--Daniel Song--Mary

Love--Allison Epic--Lili Lewd--Michelle Romance--Nina

- Look up the word in the Oxford English Dictionary, available online from the UO libraries and, no doubt, the Bodleian. Note (1) the word’s etymology, (2) the year of the earliest usage the OED lists, (3) the number of different meanings, and (4) whether any meanings are now “archaic” and what those meanings are.

- Look up the word in the Middle English Compendium, available on-line (no subscription needed). The Middle English Compendium includes the Middle English Dictionary.

- Because Middle English spelling is not regularized, you’ll need to use "wildcards" (an asterisk * instead of a vowel) in your search in the “look up” field. Besides replacing the vowels with an asterisk, put an asterisk at the end of your word. Example: for the word "affection," for instance, search for af*e*n*. The search will return all words that have those letters in that order, without regard to how many letters are BETWEEN those particular letters. Af*e*n* results in 71 hits, and brings up affeccioun, which is the spelling of the word the Middle English Dictionary uses.

- Note the MED’s etymology, earliest usage, and number of definitions. Note points of contrast/similarity with the OED definition.

- Write a brief paper (< 1000 words, hard copy) on the word's subtleties. Why might a word’s meanings change? Do a word’s historical nuances challenge your sense of language’s stability, and what effect might such recognition have on contemporary readers?

You can also be the "expert" on your word whenever it seems appropriate for class discussion. You can also highlight your word in your reading log.

2. Reading log. Keep a reading log (electronic is fine, as is paper) of your reactions to/impressions of each day’s reading assignment. Include your “word” analysis in your log. Bring your log to every class meeting: you will occasionally be required to share your log entries with others. You may include your class notes in the reading log, but please distinguish in a visible fashion between your reading log and your class notes. You can also, of course, keep your log and your notes separate.

3. Movie assignment. We’ll watch and write a short (< 1000 words, hard copy) analytical paper about Monty Python and the Holy Grail. Choose one of the film’s main points/themes and explain, using the film as “text,” how the film treats the theme. Use the language of film criticism: I’ll provide a handout.

4. A term paper (2000-3000 words, hard copy), exploring in depth an aspect of medieval love and war, concentrating on one of the texts we’re reading in the course. Keep close to the texts; find a good, specific thesis; test your ideas with your classmates and with me.

Your work for the term paper includes a term paper bibliography and group presentation. Your group will be determined by the text you choose for your term paper. I anticipate three to six groups: in other words, you must work with at least one other student. While you will work together on the group presentation, you will each research an individual aspect of the text. The idea is that, by working together, you can share bibliography and test ideas with each other. Ideally you will refine your term paper topic to something both precise and compelling. A fully-explored limited topic trumps a “from-the-beginning-of-time” topic.

For the May 26 assignment, each group will (1) compose an annotated group bibliography for their text, minimum of five academic sources (not just Internet research; hard copy given to me), and (2) present as a group why those sources are important. Remember that you’re presenting to a group of people who have read the text. Total presentation time: no more than 15 minutes. In addition, (3) each student will give me a brief individual paragraph (hard copy) describing his/her proposed thesis (about 250 words).

For our final class on June 30, each student will briefly present on his/her term paper, giving the rest of the class something to know about your research and your text. Coordinate with your group’s members so that the individual presentations have some pith.

Write down "annotations" for each research article you read. Here are some guidelines for annotation (with thanks to Prof. Lisa Freinkel):

- Cite the article or book chapter using proper MLA documentation style. The UO Library website provides guides to citation forms.

- Do more than summarize the article. Your goal here is to explicate the author's thesis as concisely and clearly as possible. Details of the argument should only be mentioned when they seem necessary for understanding the author's thesis. A good annotation will give a sense of "what's at stake" with the argument. Why is s/he writing this essay? To what critical trend or presumption is s/he responding?

- Occasionally a brief quote will be helpful to convey the author's position or his/her tone, but be careful! You want to explicate, not to re-cite. Be especially careful to paraphrase rather than quote directly if your author is using jargon, specialized or highly theoretical terms.

- Avoid editorializing. Be as neutral as possible. Your goal is not to critique but to explicate and to remember. You are presenting an argument - not demonstrating its weakness.

A medieval Web resource: The Orb

Grading

The Middle English language exercise constitutes 15% of your grade; the group presentation/bibliography/thesis paragraph, 15%; the term paper, 35%; the movie paper, 20%; contribution, 15%. . N.B.: there is no final exam in the classPlease note the University of Oregon’s "grade point value" system effective 9/90, as I will be using this system to grade your work (unless otherwise noted):

|

A+ = 4.3

|

B+ = 3.3

|

C+ = 2.3

|

D+ = 1.3

|

|

A = 4.0

|

B = 3.0

|

C = 2.0

|

D = 1.0

|

|

A- = 3.7

|

B- = 2.7

|

C- = 1.7

|

D- = 0.7

|

Note that a grade of "C" is, according to academic regulations, "satisfactory," while a "B" is "good." That means that a "B" is better than average, better than satisfactory, better than adequate. The average grade, then, is a "C"; a grade of "B" requires effort and accomplishment.

Goal: to read primary medieval literature about love and war with sensitivity to literary and cultural contexts in situ, i.e. in Great Britain.

Goal: to read primary medieval literature about love and war with sensitivity to literary and cultural contexts in situ, i.e. in Great Britain.